James Webb telescope used to spot a “larger than expected” supermassive black hole

Astronomers used the James Webb space telescope’s unprecedented capabilities to spot a true monster of a black hole. The singularity is so unexpectedly big, it disrupted its host galaxy star formation process.

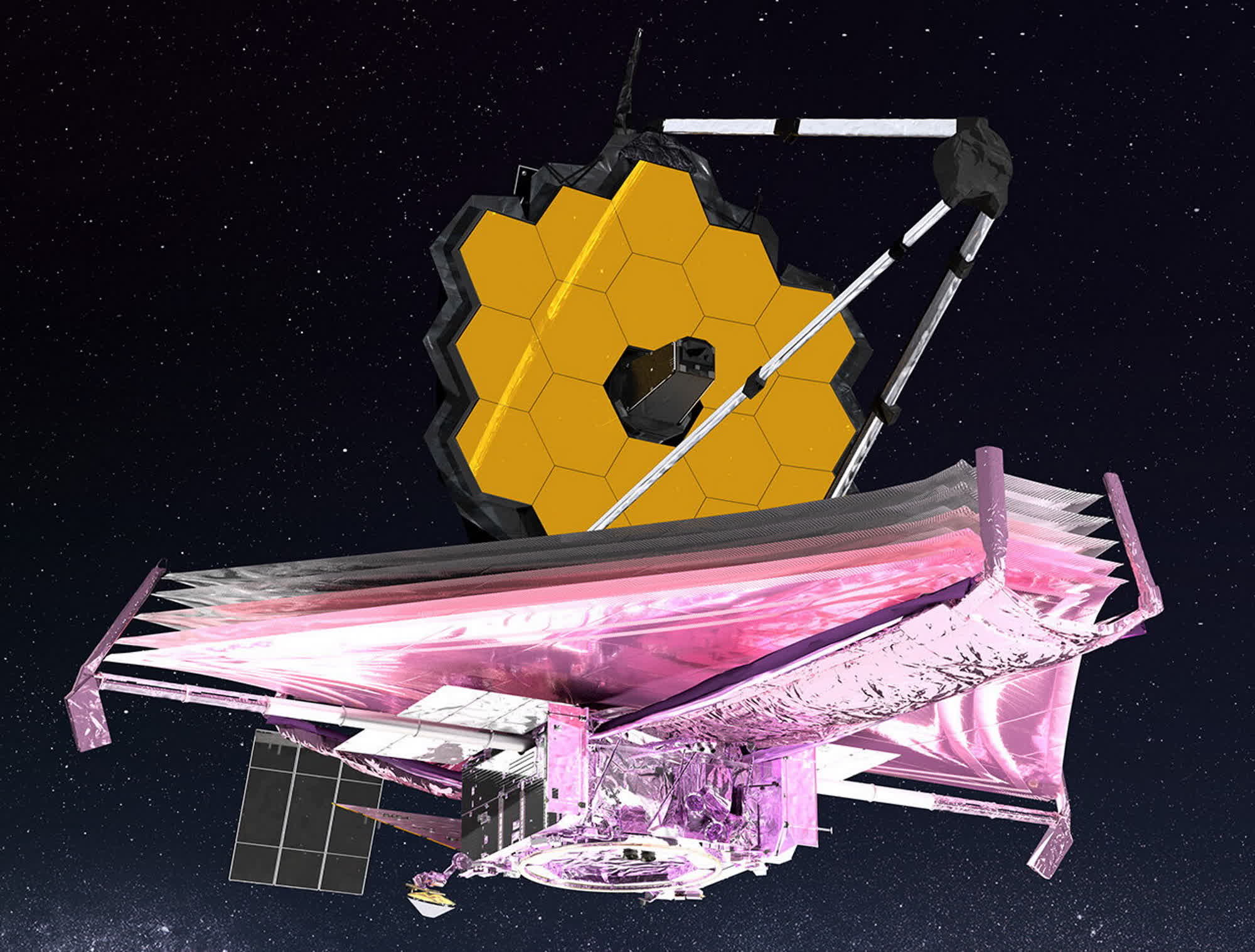

The James Web Space Telescope (JWST) is once again providing scientists around the world with never-before-seen discoveries about how the universe works. A team of researchers from Edinburgh University used the space observatory to study GS-9209, which is one of the most distant galaxies ever discovered as it lies 25 billion light-years from Earth.

According to a study published in Nature, GS-9209 is a “massive quiescent galaxy” that JWST observed in its early (billion) years, providing astronomers with the ability to chart its history in detail. GS-9209 formed as many stars as the Milky Way just 800 million years after the Big Bang, the scientists said, even though it’s one-tenth in size of our own galaxy.

Thanks to the JWST, the Edinburgh team was able to confirm that GS-9209 stopped forming new stars, as it now hosts a combined mass of 40 billion suns – which is roughly equivalent to the estimated mass contained in the Milky Way. The main culprit of the star-forming disruption is the supermassive black hole at the center of GS-9209, which is five times larger than expected for the number of stars within its host galaxy.

The “very massive” black hole at the center of GS-9209 was a “big surprise,” the scientist said, and a further confirmation of the theory predicting the star formation disruption phenomenon. Supermassive black holes can influence the creation of new stellar bodies as they release gargantuan quantities of high-energy radiation during their accretion process. Energy radiation can heat gas and drive it out of galaxies, depriving stellar nurseries within galactic nebulae of the basic fuel they need to breed new stars.

The fact that the GS-9209 black hole is so massive means that it “must have been very active in the past,” the UK researchers explained. All the energy emitted during the accretion process must have seriously disrupted “the whole galaxy,” stopping gas from collapsing to form new stars.